Building Stronger Communities: Insights from Local Economic Development Efforts in Tucson’s South 12th Avenue/La Doce Corridor

Featured photo courtesy of artists Alex! Jimenez and Johanna Martinez.

Executive Summary

Times of crisis often expose and deepen longstanding vulnerabilities in under-capitalized communities, leaving many without access to critical resources. In response to the pandemic, community-based organizations (CBOs) across the U.S. quickly mobilized to meet the critical needs of vulnerable community members.

This case study examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on neighborhood residents and businesses in Tucson’s 12th Avenue Corridor, known as La Doce. It also explores how La Doce CBOs mobilized to meet immediate needs while building towards long-term empowerment and local ownership.

Located in Tucson’s south side, La Doce is a historic majority-Latino neighborhood with Indigenous roots. Many residents have lived in the neighborhood for generations, contributing to a relatively high homeownership rate (62%). However, the neighborhood has also experienced disinvestment, and nearly one in four residents lives below the poverty line. La Doce is also celebrated for its vibrant local food, commerce, and arts economy, recognized in UNESCO’s 2016 designation of Tucson as a “City of Gastronomy.”

To study La Doce, we used quantitative and spatial data analysis, paired with historical research and two in-depth interviews with staff at the Southwest Folklife Alliance, a key cultural anchor organization.

Using quantitative data, we find:

- Disproportionate COVID-19 health impacts: From March 2020 to November 2022, COVID-19 case and death rates in La Doce were twice as high as in Pima County.

- Business stability during the pandemic: Although La Doce saw minimal new business growth between 2019 and 2023, relatively few formal businesses closed, suggesting a business corridor rooted in long-standing establishments supported by strong local ties.

- Limited federal assistance: Despite their stability, La Doce businesses received only about $1,600 per job and $500 per resident in Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) support—far less than the county averages (about $3,800 and $1,300).

In response to the compounding challenges, La Doce CBOs delivered immediate relief through mutual aid, cash assistance, and building creative cultural platforms, reinforcing the role of relational trust and local leadership in crisis response.

Our historical research and in-depth interviews revealed that:

- During COVID-19, local leaders mobilized long-standing networks of mutual aid, grassroots advocacy, and cultural organizing. Strategies included closing information gaps and rapidly launching a relief fund to disperse no-strings funds to local artists and vendors.

- Even as the community demonstrates its creative resilience, gentrification and displacement threaten its future. The expiration of COVID-era housing protections left many at risk of eviction, intensifying calls from local leaders to redefine economic success beyond GDP growth, business expansion, and land values.

- La Doce continues to use coalition-building, culture, and community networking to address long-term structural challenges. For example, CBOs like the Southwest Folklife Alliance are blending cultural museums with affordable housing and community land trusts to ensure development supports community wealthbuilding and resident stability, rather than uprooting longtime residents.

For La Doce’s Latino leaders, economic investment involves preserving cultural knowledge, supporting informal economies, and caring for marginalized neighbors. The neighborhood offers a powerful model for reimagining economic development grounded in equity, culture, and community power. The takeaway for policymakers, philanthropists, and researchers is clear: partner with community leaders in La Doce not as problems to solve but as co-creators of a just future.

Introduction

Times of crisis often expose and deepen longstanding vulnerabilities in under-capitalized communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, historically disinvested communities experienced disproportionate levels of business closures,1 unemployment,2 and housing instability.3 La Doce, a longstanding majority-Latino neighborhood in Tucson, Arizona, exemplified these patterns, having long faced poverty and displacement.

In response to the pandemic, Latino-led organizations in La Doce and across the U.S. quickly mobilized to fill governance and service delivery gaps and meet the critical needs of vulnerable members, particularly those excluded from or unable to access government relief programs such as PPP.4 From launching mutual aid networks to provide food and medicine, to creating emergency relief funds for small businesses and culture bearers, CBOs demonstrated ingenuity and commitment to community well-being. However, few studies have sought to tell the stories of the community-based efforts that sustain communities through crises. This brief combines quantitative data and cultural narratives to highlight Latino-led, community-driven responses that address both crisis and long-term empowerment.

About this Case Study

This case study is part of a series documenting Latino-led Economic Development (LLED) efforts. We define LLED as community-rooted strategies that foster economic resilience and justice through advocacy, education, access to capital, and cultural preservation initiatives. Latino leaders and organizations lead LLED efforts to ensure equitable participation and influence in the economy. These efforts are often rooted in the belief that communities can shape their economic futures through grassroots solutions centered on their cultural values and needs while fostering economic self-sufficiency.

In La Doce, LLED strategies emerged as a vital response to the compounding challenges of disinvestment, displacement, and the COVID-19 pandemic. This case study explores how community-led efforts in La Doce delivered immediate relief through mutual aid, business support, and cultural organizing while building towards long-term empowerment and local ownership.

To study La Doce, we used quantitative and spatial data analysis, supplemented by historical research and two in-depth interviews with staff at the Southwest Folklife Alliance, a key cultural anchor organization. While limited in number, these interviews provide valuable practitioner perspectives that help contextualize our findings, especially when interpreted alongside longitudinal demographic and environmental data see Appendix for additional details on methodology).

To study La Doce, we used quantitative and spatial data analysis, supplemented by historical research and two in-depth interviews with staff at the Southwest Folklife Alliance, a key cultural anchor organization. The Southwest Folklife Alliance is a cultural anchor organization that preserves, amplifies and invests in the everyday cultural expressions of diverse communities in the Greater Southwest and U.S.-Mexico Border Corridor.5 Their work centers historically marginalized voices in economic and policy decisions, recognizing culture as a foundation of economic resilience, community well-being, and self-determination.6

While limited in number, these interviews provide valuable practitioner perspectives that help contextualize our findings, especially when interpreted alongside longitudinal demographic and environmental data (see Appendix for additional details on methodology).

Traditional economic development often relies on top-down solutions and overlooks cultural and local knowledge, leading to displacement and gentrification under the guise of revitalization. In contrast, community-led strategies in La Doce empower the local informal economy, strengthen cooperative networks, and build tailored resources, paving the way for sustainable, community-centered growth for generational residents. These interventions support entrepreneurs, strengthen informal networks, and address socioeconomic disparities.

La Doce’s Histories and Context

A. Legacies of Displacement and Disinvestment in Tucson

To understand how La Doce endured the COVID-19 crisis, we must first recognize Tucson’s long history of displacement and neglect. The City of Tucson, located in southern Arizona’s Pima County, was part of Mexico until the U.S. acquired it in 1854 through the Treaty of Mesilla/Gadsden Purchase. Many residents see their ongoing ties to Mexico as a defining feature of their distinct Latino cultural identity.7 This proximity to Mexico has also been crucial to local tourism, generating hundreds of millions in annual county revenues.8

Pandemics are not new to the broader Southwest region or Tucson. The record of communicable diseases saddles Tucson’s history under Spanish, Mexican, and American control. On one side of yesteryear are Old World diseases introduced by Spaniards, like measles and smallpox. On the other side of Gadsden purchase is more smallpox, tuberculosis, and the 1918 influenza epidemic (ie. “The Spanish Flu”). Regardless of sovereign claim, these waves of infection devastated First Nation populations in Tucson.9

After the U.S. acquired the Southwest, many Mexican neighborhoods experienced economic decline due to intentional neglect and disinvestment, setting the stage for challenges still faced by low-income communities like La Doce. Meanwhile, a small number of Mexican and Mexican-American business owners rose to prominence, establishing a small Latino elite in the city that engaged in private enterprise and public philanthropy.10 Over time, growing discrimination and residential segregation sparked political advocacy in many working-class Latino neighborhoods.11

As Tucson continued to evolve throughout the 20th century, city-led modernization efforts and federal urban renewal projects brought redevelopment money to the city. By the 1960s, the city became the target for federal urban renewal projects,12 a design plan where city officials labeled neighborhoods of color “blighted” and listed for widespread demolition.13 Though these efforts brought sidewalks and other supportive infrastructure, they also erased key informal gathering spaces like small businesses exteriors and plazas, eroding the community cohesion in the name of ‘beautification.”14 These projects tore down much of the traditional city,15 displacing long-time residents and leaving a lasting impact of disenfranchisement. Generational Tucsonenses suffered under these models, especially those of color and from low-income neighborhoods. This modernization also encouraged urban sprawl, contributing to central Tucson’s decline.

Downtown Tucson revitalization efforts continued into the late 20th century, bringing continued benefits for some and displacement for many. Between 1996 and 2004, Tucson received three U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Hope VI Revitalization Grants,16 including the Martin Luther King Apartments, Robert F. Kennedy Homes, and Connie Chambers. In addition to these efforts, central Tucson became the focus of varied economic revitalization tools such as Opportunity Zones, other HUD investments, and Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). Throughout the 20th century, Latino neighborhoods like La Doce continued pushing for inclusive investments while building their own strong economic communities.

B. Location and Cultural Identity of La Doce

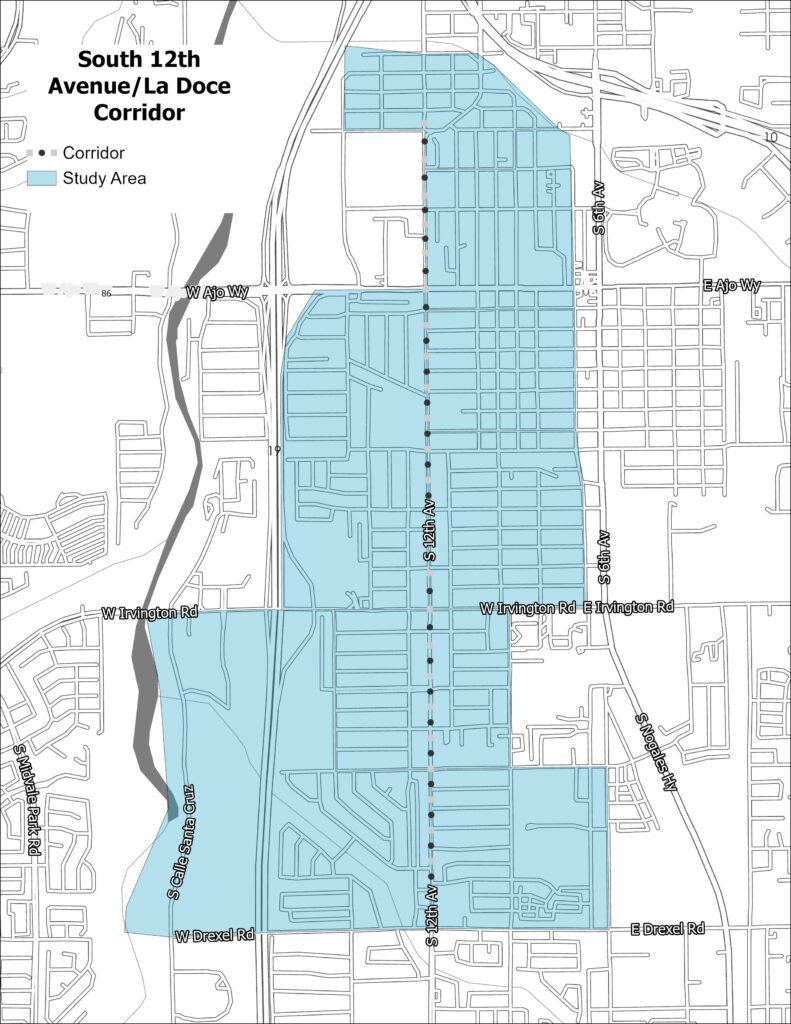

Located in southern Tucson, La Doce spans three miles along South 12th Avenue from 44th Street and Drexel Road and sits near two major transportation corridors, including the planned Tucson Norte-Sur High Capacity Transit (HCT) corridor (see Map 1).17 The dotted line on the map shows the 12th Avenue business corridor, while the blue shaded polygons indicate the surrounding Census block groups used to provide demographic and socioeconomic data for La Doce.

Map 1. La Doce Corridor Boundaries (Defined by Census Block Groups)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Cartographic Boundary Shapefile.

Urban planners and advocates describe La Doce as a “naturally occurring cultural district” shaped by a vibrant local economy rooted in food, commerce, and the arts.18 UNESCO’s 2016 designation of Tucson as a “City of Gastronomy” reinforced this identity, recognizing its unique culinary heritage, much of which is represented in La Doce.19 However, Alisha Vásquez, communications and accessibility director at the Southwest Folklife Alliance, expresses her concerns that recent culturally-oriented economic development efforts have been more focused on increasing tourism than centering the needs of current residents:

“It’s said, you know, arts and culture bring X amount of dollars to Tucson every year. [But] it’s all focused on outsiders, right? It’s all focused on tourism. It’s not really focused on those of us who are here every day and will be here until the day we die. So there’s that disconnect.”

Unlike the more resourced downtown core, Tucson’s South Side has historically lacked targeted public and private investment, leaving communities like La Doce particularly vulnerable to poverty, gentrification, and displacement from speculative development.20 The consequences of such chronic underinvestment for ordinary people translates into compounded and disproportionate exposure to community-wide crises, like the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Neighborhood Conditions in La Doce Today

A. La Doce’s Demographics as Motivation for Cultural Strategy

La Doce’s demographic profile helps explain why community-based service delivery, cultural preservation, and Latino-led economic development are central to the neighborhood’s resilience and growth. As shown in Table 1, most of La Doce’s 12,000 residents identify as Latino or Hispanic (88%), more than twice the share found in Tucson City (43%) and Pima County (36%).

A closer look at La Doce’s Latino population by race shows that 6% of La Doce Latinos identify as Native American or Indigenous, 21 more than twice the rate in Tucson and Pima County. Nearly one in ten (9%) residents identify as Native American, regardless of ethnicity. Race demographics help explain why service providers emphasize traditional artists and cultural bearers in a largely Indigenous and Latino neighborhood.22

Table 1. Racial and Ethnic Composition of La Doce Neighborhood, 2023

Note: Latinos can be of any race. All other groups reflect the non-Latino/non-Hispanic population.

Source: LPPI analysis of 2023 5-Year American Community Survey Table B03002, available online.

La Doce residents are also far more likely to speak Spanish at home (Figure 1). Over three-quarters of La Doce residents are primarily Spanish-speaking households (76%), about three times the rate for Tucson (27%) and Pima County (23%). Further, 15% of La Doce households are Spanish-speaking and limited English proficient—meaning no household member speaks English “very well”23—which is five times the city and county rate (3% for both). These language differences shape service delivery, community building, and economic development strategies.

Figure 1. Household Language in La Doce, Tucson, and Pima County, 2023

Share of Total Households

Note: Limited English proficient households are defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as those in which no member 14 years old and over 1) speaks only English or 2) speaks a non-English language and speaks English “very well.”

Source: LPPI analysis of 2023 5-Year American Community Survey Table C16002, available online.

La Doce residents have much lower formal education levels than city and county averages (Figure 2). Almost one third of La Doce residents (32%) did not complete high school, more than double the rate for Tucson (13%) and more than triple the rate for Pima County (10%). Only 7% of La Doce residents completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 30% of Tucsonans and 36% countywide. These educational disparities contribute to economic hardship.

Together, these demographic patterns underscore the need for community strategies that prioritize linguistic access, cultural representation, and equity in service delivery. In La Doce, cultural preservation is not only about identity—it is a strategy for economic and social sustainability.

Figure 2. Educational Attainment for the Population 25 and Over in La Doce, 2023

Source: LPPI analysis of 2023 5-Year American Community Survey Table B15003, available online.

B. Intergenerational Homeownership amid Economic Struggles in La Doce

La Doce is a majority-Latino, working-class community facing significant economic challenges despite a relatively high homeownership rate. With 62% of households owning their homes—compared to 52% in Tucson—La Doce stands out as a historically affordable neighborhood for low- and moderate-income families (Table 2). This suggests La Doce served as a low-cost ‘opportunity neighborhood,’ providing residential stability over time.

While quantitative data on multigenerational housing are unavailable, local leaders interpret La Doce’s high homeownership rate as a reflection of strong family networks and intergenerational support systems. As Nelda Liliana Ruiz Calles, project manager for cultural organizing at the Southwest Folklife Alliance, explains:

“The relationship piece is very centered in our community, and the respect and cariño (affection) for one another is very big in the south side of Tucson. The high homeownership further proves how generations are very supportive of one another here…That’s very big in our community here in Tucson. The whole family is involved and it’s important for everybody to come to the decision table.”

Yet this homeownership stability is increasingly under threat. The median household income in La Doce is just over $40,000—about $14,000 lower than the city median and $17,000 lower than the county average—indicating significant income disparities that may limit future access to homeownership. Moreover, 24% of residents live below the poverty line, a rate substantially higher than both the city and county.

Though the median gross rent of $930 is lower than city and county averages, it remains burdensome given income levels. Ruiz points to rising rents, external investment patterns, and speculative land ownership as growing threats that are reshaping the homeownership opportunity landscape in La Doce:

“In the south side of Tucson we have a lot of vacant lots…the majority of those vacant lots weren’t even owned by humans. They’re owned by hedge funds in Washington and New York…We’re [also] seeing the hoarding of land waiting for the speculative market to come in…to price us out. We’ve been seeing those seeds of gentrification already in our community for the last five years. But it’s definitely more intense right now.”

Interviewees described growing concern among residents that economic forces are eroding La Doce’s legacy of homeownership and familial rootedness, underscoring the urgent need for strategies that protect long-term residents and sustain community-defined economic development.24

Table 2. Homeownership and Income Indicators for La Doce, Tucson, and Pima County, 2023

Source: LPPI analysis of 2023 5-Year American Community Survey data, available online.

C. Environmental Injustice and Public Health Risks in La Doce

Rising housing costs in La Doce are paired with serious environmental health risks. Partly due to its location between two major highways, the neighborhood experiences high levels of air pollution. La Doce’s exposure to Diesel Particulate Matter (PM) is 56% higher than the Pima County average (Table 3), while its PM2.5 exposure is 6% higher.25 These conditions have led to La Doce’s designation as a disadvantaged area under the federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST 2.0), which identifies communities facing heightened environmental and socioeconomic burdens.

Table 3. Environmental Indicators for La Doce

Source: LPPI analysis of data from Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool, accessed May 2025.

Today’s pollution mirrors La Doce’s long environmental justice struggle. In the late 1940s, the Hughes Aircraft Company and other defense contractors began dumping trichloroethylene (TCE),26 a metal-cleaning solvent, into local drains and soil.27 Later testing by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found unsafe TCE levels in well water, and many South Side residents—including residents in La Doce—were diagnosed with cancers linked to this contamination.28 In 1989, the City of Tucson settled a lawsuit filed by 1,600 residents for $35 million; by 2006, the final insurance settlements brought the total payout to over $130 million.29

“At the time, we didn’t use military-industrial complex language, but with reflection we are now looking at how something that happened 70 years ago is still happening today with other types of contaminants,” said Alisha Vásquez, the communications and accessibility director at the Southwest Folklife Alliance. Alisha is also the co-director of the Mexican American Heritage and History Museum in Tucson, which is organizing a year-long retrospective on groundwater contamination that started in the 1940s during the military-industrial advancement.

D. Grassroots Economies and Cultural Entrepreneurship

In addition to a multigenerational community, La Doce boasts a vibrant, neighborhood-serving economy. In 2023, 341 registered businesses operated within a quarter-mile buffer along South 12th Avenue (Map 2).30 Three quarters (75%) were microbusinesses with between one and nine employees, with few large establishments.

Map 2. South 12th Avenue/La Doce Business Corridor

Note: Each pin represents a business establishment. The surrounding blue buffer boundary reflects the areas of analysis.

Source: LPPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Cartographic Boundary Shapefile and LPPI analysis of 2023 data from Data Axle.

Retail trade businesses—such as small Mexican markets, clothing shops, and construction supply stores—make up 20% of local business establishments (Figure 3). This diverse industrial mix reflects La Doce’s role as a commercial hub, offering essential services such as food, beauty, and construction supplies.

Figure 3. Business Sectors in South 12th Avenue/La Doce Corridor, 2023

Notes: Industries reflect two-digit NAICS sectors. Data reflect businesses in a quarter-mile buffer area along the South 12th Avenue corridor. In 2023, there were 338 total businesses in the corridor.

Source: LPPI analysis of 2023 Data Axle data.

Community stakeholders’ ethnographic and participatory action research highlights that “an organic culture of food entrepreneurship exists, but credit and institutional obstacles impair growth.”31 Alisha Vásquez at the Southwest Folklife Alliance adds that La Doce’s unique economy allows the community to define success on its own terms, rooted in cultural expression and informal networks:

“During the pandemic, we saw more corporate development in areas with a strong history of local business. La Doce was one of the few that resisted this trend…There’s still a strong emphasis on immigrant and undocumented businesses—what we call the sub-economy. That’s part of our economic power.”

COVID-19’s Impacts on La Doce

The pandemic exposed deep-rooted inequities in health, access, and opportunity in La Doce. High infection and death rates were driven by limited healthcare access, environmental risks, and systemic disinvestment.

A. Disproportionate COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in La Doce

Between March 2020 and November 2022, La Doce recorded some of the region’s highest COVID-19 case and death rates. For example, Tracts 24, 25.01, 38.01, 38.02, and 39.01 fell within the highest tiers of cumulative infections (Map 3).

Map 3. Cumulative COVID-19 Cases in La Doce and South Tucson, March 2020 to November 2022

Note: Darker colors represent higher cumulative totals.

Source: Pima County Public Health Department (2024), available online.

COVID-19 case rates in La Doce were nearly twice as high as Pima County’s, 43,800 per 100,000 versus 28,600. Similarly, COVID-related death rates in La Doce were over twice as high as they were countywide, at about 800 per 100,000 residents, compared to nearly 400 per 100,000 countywide.32 Much of the area is designated a Medically Underserved Area by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, indicating limited access to primary care providers and other health care services.33

Figure 4. COVID-19 Infection and Death Rates per 100,000 Residents in La Doce and Pima County, March 2020 to November 2022

Note: Data for La Doce reflect rates for Census Tracts 24, 25.09, 38.01, 38.02, and 39.01.

Sources: LPPI analysis of data from the Pima County Health Department, available online; and 2018-2022 5-Year American Community Survey.

B. Local Business Stability Despite Unequal Federal Assistance

The pandemic affected all aspects of community life, including La Doce’s local business landscape. While the pandemic’s health impacts were severe, the economic effects tell a more complex story.

Central to the community’s cultural and economic fabric, small businesses endured significant pandemic-related challenges but remained surprisingly stable (Figure 5). Between 2019 and 2023, La Doce saw minimal net business growth (2%) compared to 10% countywide. Entry and exit rates were relatively balanced at 26% and 23%, respectively). The overall “churn rate,” or combined business entries and exits, was lower than the county average (49% vs. 59%). This suggests a corridor rooted in long-standing establishments supported by strong local ties.

Figure 5. Business Dynamics in La Doce and Pima County, 2019 to 2023

Note: Data for La Doce reflects the quarter-mile buffer area as shown in Map 2. Data span the periods before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Entry and exit rates refer to the percentage of businesses that opened and closed respectively.

Sources: LPPI analysis of 2019 and 2023 Data Axle data.

However, La Doce received little federal pandemic relief. La Doce received only about $1,600 per job and $500 per resident in Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) support—far less than the county averages ($3,793 and $1,344, respectively; Figure 6). Language barriers, informality, and an inability to access applications likely contributed to the gaps in PPP funding. As Nelda Ruiz noted,

“Not all families had stable internet access or flexible work schedules or formal documentation to receive federal aid…federal and state relief programs often required documentation, whether it be Social Security numbers or formal business licenses, [and] that excluded so many of our community, like undocumented entrepreneurs, street vendors, and cultural workers.”

Figure 6. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Relief Received in La Doce, Pima County, and Arizona

Sources: LPPI analysis of PPP data from U.S. Small Business Administration data (2024), available online.

Population data are from the 2017-2021 5-Year American Community Survey. Job data are from the 2019 Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD) dataset.

Distrust of Traditional Economic Development and Unequal Investment

“Folk traditions, mutual aid networks, and informal economies are often overlooked as legitimate sites of investment.” – Nelda Ruiz

Despite urgent financial needs, many La Doce residents remain weary of economic development due to past disappointments. In 1999, a Tax Increment Financing (TIF) district called Rio Nuevo was expected to benefit local communities but ultimately failed to deliver.34 According to Alisha Vásquez, the tax district was supposed to “bring lots of services to the West Side and Downtown, which are historic Mexican-American neighborhoods, but they let the community down, leaving a horrible taste in the mouth of everyone when you bring up Rio Nuevo, especially our elders.” Since the pandemic, new efforts to improve neighborhood walkability, transit, and property rehabilitation have been funded by the city of Tucson, state and federal grants, foundations, and universities.35

Recent revitalization efforts, though better resourced, continue to raise concerns, particularly about neighborhood change such as gentrification. In 2016, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) assigned the National Association for Latino Community Asset Builders (NALCAB) to assist the City of Tucson in assessing La Doce’s socioeconomic conditions, aiming to build on the strong local micro-economy.36 Still, residents remain skeptical. Alisha Vásquez noted:

“…There’s been a lot of investment in our historic barrios (neighborhoods) but it’s been the kind of investment that is welcoming gentrification. I don’t know yet how you invest in an area without gentrifying it. Because inevitably, if you build a better bike lane more people are going to use it.”

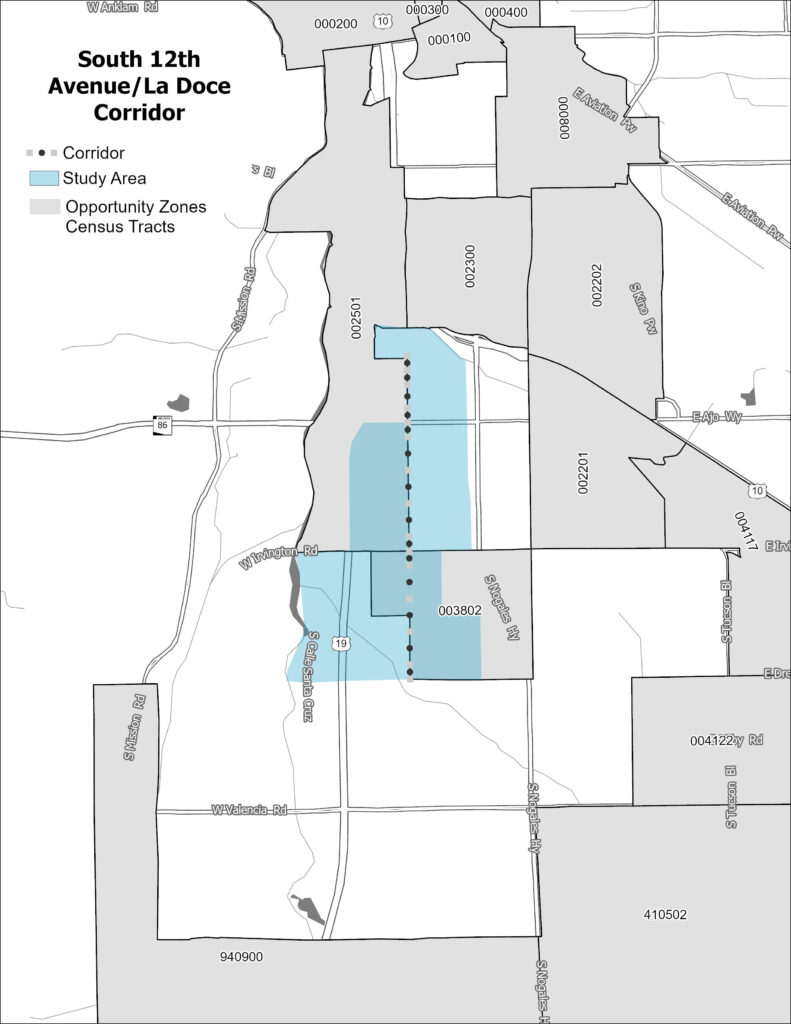

Today, two of La Doce’s census tracts are designated Opportunity Zones (See Map 4), offering tax incentives for investments in eligible, historically underserved neighborhoods.37 However, La Doce has seen little benefit, and Tucson as a whole has received less Opportunity Zone investment per resident than other comparable regions.38 Furthermore, research on Opportunity Zones suggests this economic development tool has had minimal impact on residents’ employment, earnings, or poverty,39 and investments tend to favor wealthier, more educated counties.40

Map 4. Federally Designated Opportunity Zones in La Doce

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, available online.

Top-down economic revitalization and development efforts often promise benefits like increased revenue for local businesses, improved livability for residents, and new opportunities for work and leisure. Historically, however, top-down approaches have displaced existing businesses and residents.41 Because of Tucson’s southside past experiences with top-down projects, La Doce community organizers advocate for culturally grounded strategies such as micro-loans, startup grants, financial training, and reduced bureaucracy, especially for immigrant, informal, and home-based businesses. As Nelda Ruiz emphasized, “Community ownership and economic sovereignty [are important to us because] our people don’t have the same access to capital as our counterparts [in other communities].”

Interventions: Mutual Aid, Community Powerbuilding, and Wealth Building

In the face of compounding crises—from a deadly pandemic to rising displacement—La Doce community leaders drew on decades of cultural organizing, mutual aid, and grassroots advocacy to respond swiftly and collectively. As interviews with the Southwest Folklife Alliance staff confirmed, these interventions were not simply reactions to the crisis but extensive, long-standing networks of care, cultural resilience, and a shared commitment to community self-determination.

A. Community Networks and Community-Led Mutual Aid during the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Tucson’s mutual aid networks rooted in cultural traditions and cross-border solidarity activated quickly. Collectives like Regeneración closed information gaps with reliable updates, while other organizations closed public health resource gaps by distributing personal protective equipment (PPE). Businesses also leaned on longstanding connections, finding resilience not in federal relief but in shared community strength and values, prioritizing relationships, family, and cultural continuity. Nelda Ruiz explains:

“We were very much about building and continuing and nurturing those longstanding relationships that we’ve had in the barrio for almost over 20 years, and ensuring that [residents] knew about the city relief programs and ensuring they had access to PPE.”

CBOs also played an essential role in collecting and distributing financial resources to residents and local businesses, particularly those excluded from traditional support systems. While Tucson and Pima County received over $335 million in American Rescue Plan funds, La Doce received disproportionately little PPP support, as many immigrant and informal businesses lacked access or eligibility.42 In response, CBOs launched mutual aid efforts, delivering unrestricted cash assistance to informal businesses, elders, people with disabilities, and cultural workers. Ruiz shared how the Southwest Folklife Alliance rapidly launched a relief fund, dispersing 20 no-strings awards of $500 each to local artists and vendors in the region. They also created LOOM Market, a no-fee online sales platform for artists to sell safely. Many artists were elders, disabled, and from rural communities. These informal support systems helped sustain the local economy amid widespread federal neglect.

The Southwest Folklife Alliance also pivoted its spaces for community building to meet urgent needs. For example, the folklife festival “Tucson Meet Yourself” offered income and revenue opportunities to local vendors, services and resources for families, and a space for CBOs and elected officials to hear about local needs.43 “This work wasn’t just about mitigating the crisis,” said Ruiz. “It was about reinforcing care, autonomy, and cultural survival to shape future development.” Ruiz further explained Regeneracion’s focus on mutual aid:

“[Regeneración] focused on mutual aid. We partnered with different agencies, with different organizations, and with the city to redistribute Federal relief monies to our families who didn’t qualify for whatever barrier. We distributed over $1.7 million dollars back to the families in Tucson’s South Side, which is where we’re based…We’ve been a part of mutual aid networks even before the pandemic, but [COVID-19]…strengthened our coalition building between different civic partners, organizations, and serving agencies, recognizing the power of helping one another.”

Vásquez added that Tucson’s history of cross-border mutual care laid a foundation for mutual care during the pandemic, as many families and communities in the area were already experienced with supporting each other across borders, especially when there was little federal support for immigrants:

“In Tucson, the 1994 border [got] closed off, and with the curation of checkpoints becoming normalized after 9/11, there’s a lot of historical knowledge that we have here. And so I just think that those networks were in place, so we knew how to do mutual aid.”

Despite limited federal support, La Doce’s strong networks and community ties became the civic infrastructure for pandemic response, economic resiliency and social cohesion. Longstanding relationships and community connection to each other allowed the neighborhood to sustain itself amid economic stress, disinvestment, and systemic neglect. For instance, The Southwest Folklife focused on low-tech, high-accessibility platforms to ensure tradition bearers could still participate in cultural and economic life. As Nelda Ruiz stated:

“Mainstream definitions of success are often focused on GDP, growth and job creation, and business expansion, which is very important. But I think, for Latine communities, success also means a lot of different things that are belittled and ignored and invisible…like asset building in nontraditional ways. The ability to pass down cultural knowledge, sustain family-run businesses or keep local economies informal, but yet continue to thrive, is huge—our systems of care. A lot of us are able to care for our families that live on the other side of the border…of our elders. We don’t brush them off once they get old, there’s a lot of care, cariño, and respect that comes from within the Latine community, and that is also a way to measure success.”

B. Community Power and Wealth Building: Past, Present, and Future

La Doce has a long history of community organizing and advocacy. Residents and business owners organized for change long before external agencies showed interest in the neighborhood. For instance, the grassroots group Tierra y Libertad Organization (TYLO), today known as Regeneracíon, champions “barrio sustainability,” recognizing the value of what residents already do. In collaboration with other organizations, Regeneracíon offers Spanish-language training on city ordinances and budgets.

The 2017 La Doce Barrio Foodways Project—a collaboration of Regeneración and the Southwest Folklife Alliance—furthered a vision for change by training over 20 young residents to document how food and culture shape community identity and resilience. Citizen ethnographers served as community researchers, looking beyond stereotypes to map informal assets and markets in the area. The research concluded with a call to establish new models of community governance and wealth creation–a Community Land Trust, a Fund, and an inclusive Community Council. Today, the Southwest Folklife Alliance and Regeneración have acquired land to bring the land trust to life. Regeneración is currently working with 15 families to establish the trust.

Art and culture remain central tools for resistance and empowerment in La Doce. Local Chicano and Latino artists, musicians, and other tradition bearers have led efforts to preserve community identity for new generations. Groups like the Southwest Folk Alliance connect residents to activism, research, and policy through cultural programming and help artists showcase their work. Museums such as the Mexican American Museum also uplift local residents’ history of activism and advocacy. Staff imagine even deeper partnerships between art, cultural institutions, and supportive services for marginalized residents: “I would build a new space…exhibition space and community rooms…above affordable housing for people of color and people with disabilities,” shared Alisha Vásquez, who is also the Mexican American Heritage and History Museum museum’s Co-Director. “I want to be more creative in investing.”

In 2022, the Southwest Folklife Alliance launched the La Doce Space Activation to reinforce local powerbuilding. While networks of care already existed, the urgency of COVID and new development pressures created opportunities for dialogue and planning.

Facing gentrification and rising rents, residents continue to advocate for development that centers their needs. They emphasize assets, not deficits—cultural identity and the informal economies that define La Doce. With business training, capital, and reduced red tape, these enterprises can thrive. “How do you asset map to see what’s here to protect the most vulnerable or to create space for folks who might not be able to enter those spaces as easily as we do?” asked Vasquez. “And kind of flip those power dynamics.”

“Going back to the importance of knowing your neighbors and building support networks by those relationships, to quote Adrienne Marie Brown, “we move at the speed of trust”,” added Ruiz. “This work takes a long time, especially during moments of crisis, so it’s important to have those solid networks in place. So because you’re already a part of that network, you don’t have to start from zero. It’s so easy to discredit and belittle those relationships that to Latine people mean everything.”

Conclusion: Toward a More Equitable Future for La Doce

La Doce remains a powerful example of the resilience Latino communities across the U.S. demonstrate in the face of ongoing disinvestment. Bordered by highways and anchored by generations of working-class Latino and Indigenous families and businesses, La Doce has long been excluded by traditional economic development efforts. Residents have faced decades of environmental contamination, housing instability, and neglect. Yet the community has sustained itself through intergenerational homeownership, tight social networks, and a vibrant local economy rooted in foodways, cultural expression, and informal businesses.

The COVID-19 pandemic laid these vulnerabilities bare, with La Doce experiencing some of the region’s highest infection and death rates. Federal aid programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program largely bypassed the immigrant and undocumented entrepreneurs who are vital to the local economy. In response, community organizations such as the Southwest Folklife Alliance and Regeneración mobilized mutual aid, cash assistance, and creative cultural platforms, reinforcing the role of relational trust and local leadership in crisis response.

Yet even as the community demonstrates its creative resilience, gentrification and displacement threaten its future. The expiration of COVID-era federal and state emergency rental assistance and eviction moratoria left many low-income households vulnerable to eviction. These realities intensified calls from local leaders to redefine economic success beyond traditional metrics such as GDP growth, business expansion, and land values.

For La Doce residents, economic success means preserving cultural knowledge, sustaining informal economies, and ensuring families can care for one another across generations and borders. Local advocates are advancing creative solutions—like blending cultural museums with affordable housing and community land trusts—to ensure development supports rather than uproots those who built La Doce. They also call for continued partnership with researchers and advocacy groups who center lived experiences and intergenerational leadership, modeling an alternative to exploitative university-community engagement that have characterized past academic initiatives in this space.

La Doce exemplifies how Latino communities across the country are not only responding to structural harm but also reimagining economic development through equity, cultural identity, and community power. The takeaway for policymakers, philanthropists, and researchers is clear: partner with communities like La Doce not as problems to solve, but as co-creators of a just future. As Ruiz concluded, “We are movement builders, and through our work we ensure that economic strategies are culturally relevant and rooted in community knowledge, traditions, and ways of relating to land, labor, and resources…We center cooperative solidarity-based economies that uplift the collective, rather than prioritize individual success, and funders [need to] recognize that alternative models should be invested in.”

Acknowledgments

The research team extends its gratitude to Sonja Diaz for setting the project’s vision, Alberto Murillo for early literature review support, Julia Silver for reviewing an earlier version of this report, Citlali Tejeda for visual and editorial support, Jorge Padilla and Bryzen Enzo Morales for research support, and Jared Jimenez for support with cartography. We would also like to thank Alisha Vásquez and Nelda Ruiz of the Southwest Folklife Alliance for their time and commitment to this project.

Appendix

We used a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and spatial data analysis, historical research, and qualitative interviews. The interviews—limited to two staff members from the Southwest Folklife Alliance—were not intended to be representative but instead to offer practitioner insight from individuals deeply embedded in La Doce’s cultural and economic life. These perspectives helped us interpret the broader data trends and identify locally relevant themes. We acknowledge that the small sample size limits the generalizability of the qualitative findings and invite further study to build upon this exploratory case. Future research should include a broader sample of community voices to deepen and validate the themes identified here.

Interviewers asked community leaders about their organization’s background and mission; strategies and stories of COVID-19 resilience; specific needs, values, or opportunities they see as necessary to building a strong local economy; systemic barriers encountered when trying to implement Latine-centered strategies; lessons on productive Latine leadership, and visions for the future. While not exhaustive, these interviews provided context to interpret the stories underlying the quantitative data and better understand on-the-ground experiences.

Quantitative sources included:

- 2019-2023 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates data on population, race and ethnicity, household income, housing tenure, and rent to describe La Doce’s demographics and economic conditions.44

- Climate Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) 2.0 indicators of pollution exposure and environmental risk.

- 2019 and 2023 Data Axle establishment-level data to assess business dynamics pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic. We calculated business entry and exit rates, net change rates, and churning rates of businesses from 2019 to 2023 to better understand neighborhood business dynamics.45

We also gathered data from several historical sources. Historical resources include the online repository of the Mexican Heritage Project photos in the Arizona Historical Society Library and Archives in Tucson. Lastly, we gathered information on investment zones and designations over time using the archives of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the U.S. Department of Treasury Community Development Financial Institutions Funds to investigate the area’s funding and planning history.

End Notes

1 “COVID-19 Impacts on Minority-Owned Small Businesses in California,” UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge, December 2020, available online; Robert Fairlie, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Owners: Evidence from the First Three Months after Widespread Social-Distancing Restrictions,” Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 29, no. 4 (2020): 727-40, available online.

2 U.S. Small Business Administration, The Impacts of COVID-19 and Racial Disparities in Small Business Performance (Washington, DC: U.S. Small Business Administration, August 2022), available online.

3 Paula Nazario, Silvia R. González, and Paul M. Ong, Latino and Asian Households in California are Behind on Rent and Behind in Access to State Relief Program (Los Angeles: UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute and UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge, April 4, 2022), available online; Shreela V. Sharma, Ru-Jye Chuang, Melinda Rushing, Brittni Naylor, Nalini Ranjit, Mike Pomeroy, and Christine Markham, “Social Determinants of Health–Related Needs During COVID-19 Among Low-Income Households With Children,” Preventing Chronic Disease 17 (October 2020): 200322, available online.

4 Paul M. Ong, Silvia R. González, Chhandara Pech, Kassandra Hernández, and Rodrigo Domínguez-Villegas, Disparities in the Distribution of Paycheck Protection Program Funds Between Majority-White Neighborhoods and Neighborhoods of Color in California (Los Angeles: UCLA Latino Policy and Institute, December 17, 2020), available online.

5 Southwest Folklife Alliance, “History,” accessed May 27, 2025, available online.

6 Southwest Folklife Alliance, “Mission,” accessed May 27, 2025, available online.

7 Thomas E. Sheridan, Los Tucsonenses: The Mexican Community in Tucson, 1854-1941 (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1986); Arizona State Library, “The Mexican Heritage Project,” accessed June 22, 2025, available online.

8 Visit Tucson, Annual Report FY24 (2024), available online.

9 Thomas E. Sheridan, Los Tucsonenses; Desert Archaeology, Inc., “We Have Been Here Before: A History of Epidemics in Southern Arizona,” April 8, 2020, available online.

10 Thomas E. Sheridan, Los Tucsonenses.

11 Ibid.

12 Juan Gomez-Novy and Stefanos Polyzoides, “A Tale of Two Cities: The Failed Urban Renewal of Downtown Tucson in the Twentieth Century,” Journal of Southwest 45 (2003): 87, available online.

13 Lydia R. Otero, La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, November 2010).

14 Andrew Adkins, Gabriela Barillas-Longoria, Deyanira Nevárez, and Maia Ingram, “Differences in Social and Physical Dimensions of Perceived Walkability in Mexican American and Non-Hispanic White Walking Environments in Tucson, Arizona,” Journal of Transport & Health 14 (2019): 100585, available online.

15 Ibid.

16 “HUD Revitalization Tracker,” UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, June 2023, available online.

17 See also AZPM, “La Doce — South 12th Avenue Tucson Neighborhood,” YouTube video, uploaded on March 31, 2023, available online.

18 Southwest Folklife Alliance, La Doce, Barrio Foodways: A Report on Community Knowledge and Recommendations for Sustainable Change in Tucson, Arizona (Tucson, AZ: Southwest Folklife Alliance, 2017), available online.

19 AZPM, “La Doce — South 12th Avenue Tucson Neighborhood”; Andi Berlin, “Eat Your Way Through South 12th Avenue at These Chef-Approved Mexican Food Spots,” This is Tucson, October 23, 2019, available online.

20 Warren Bristol, Quinton Fitzpatrick, Ariel Fry, Julian Griffee, David Jellen, Samuel Jensen, Lena Porell, Andrew Quarles, Lindsey Romaniello, and Yicheng Xu, Tucson Displacement Study: A Planning Study of Tucson Neighborhoods and Displacement (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, 2020), available online.

21 “Indigenous Latino” refers to individuals who identify as Hispanic or Latino in the ethnicity question and “American Indian and Alaskan Native” in the race question.

22 Elliott D. Pollack & Company, Tucson Market Assessment (Tucson, AZ: City of Tucson, 2021), available online; Southwest Folklife Alliance, “La Doce,” January 1, 2022, available online.

23 U.S. Census Bureau, “What Languages Do We Speak in the United States?,” December 2022, available online.

24 Diana Ramos, “This Community on Tucson’s South Side is Changing the Narrative,” Tucson.com, August 22, 2023, available online.

25 The federal standard for PM2.5 is an annual average of 9 µg/m³. There is no state or federal standard for diesel PM. Diesel PM is a significant component of PM2.5 and is linked to serious health impacts, including respiratory and cardiovascular issues. Exposure to diesel PM has been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer and can worsen conditions such as asthma and chronic bronchitis. While PM2.5 is regulated by the government, diesel PM is not. Diesel PM can originate from a variety of sources, including vehicles, trucks, buses, wildfires, and other forms of combustion-related exhaust present in the environment.

26 Pima County Public Library, “Pollution in Tucson Water,” accessed June 22, 2025, available online.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 While many are registered businesses, several La Doce businesses operate informally and are not captured in official registries. For business dynamics, we focused on a quarter-mile buffer along South 12th Avenue because the area was identified by local community partners as representing the core business corridor of La Doce.

31 Southwest Folklife Alliance, La Doce, Barrio Foodways.

32 Rates for La Doce were calculated using cumulative COVID-19 case and death data (March 2020 to November 2022) from the Pima County Public Health Department and ACS 2018–2022 population estimates. Figures reflect Tracts 24, 25.09, 38.01, 38.02, and 39.01. Countywide rates use official totals and did not require tract-level aggregation.

33 Based on a spatial overlay of the La Doce study area boundary (defined by census block groups) with the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Medically Underserved Area shapefile, available online.

34 Rio Nuevo District, “What is Rio Nuevo?,” accessed June 22, 2025, available online.

35 City of Tucson, “La Doce: Current, Potential, & Completed Efforts Summary, Planning & Development Services Department,” February 14, 2020, available online.

36 Elliott D. Pollack & Company, Market Assessment of South 12th Avenue Corridor (Tucson, AZ: City of Tucson, 2021), available online.

We look at Opportunity Zones as one recent measure or aspect of economic development in the United States, but it is not the only vehicle through which place-based investment can be made.

38 Patrick Kennedy and Harrison Wheeler, “Neighborhood-Level Investment from the U.S. Opportunity Zone Program: Early Evidence,” UC Berkeley Opportunity Lab, April 12, 2021, available online.

39 Matthew Freedman, Shantanu Khann, and David Neumark, “JUE Insight: The Impacts of Opportunity Zones on Zone Residents,” Journal of Urban Economics 33 (2023): 103407, available online.

40 Kevin Corinth, David Coyne, Naomi Feldman, and Craig Johnson, “Chapter 7. The Targeting of Place-Based Policies: The New Markets Tax Credit Versus Opportunity Zones,” in The Economics of Place-Based Policies (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming), available online

41> Karen Chapple and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Transit-Oriented Displacement or Community Dividends? Understanding the Effects of Smarter Growth on Communities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), available online; Gerardo Francisco Sandoval, “Planning the Barrio: Ethnic Identity and Struggles over Transit-Oriented, Development-Induced Gentrification,” Journal of Planning Education and Research Vol. 41(4): pp. 410-424, available online.

42 The City of Tucson received $135.7 million in funds from the American Recovery Plan Act, while Pima County received $203 million. For more details, see City of Tucson, “State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds 2022 Report,” June 30, 2022, available online; and Pima County, “American Rescue Plan Act Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds 2023 Report,” August 1, 2023, available online.

43 Tucson Meet Yourself, “Tucson Meet Yourself,” Accessed July 10, 2025, available online.

44 We use the following Pima County, Arizona block groups to provide socioeconomic data on La Doce: Block Groups 2 and 4, Census Tract 24; Block Group 1, Census Tract 25.09; Block Groups 1 and 2, Census Tract 38.0; Block Groups 1 and 2, Census Tract 38.02; and Block Group 1, Census Tract 39.01.

45 For business dynamics, we focused on a quarter-mile buffer along South 12th Avenue because the area was identified by local community partners as representing the core business corridor of La Doce.